When a crisis call involves a person with an intellectual and/or developmental disability (IDD), the usual mental-health playbook isn’t enough. What appears to be noncompliance may actually be due to slow processing. What sounds like agitation may be sensory overload. And what seems like defiance might be self-protection in a noisy, frightening environment.

If responders bring speed, volume, and command presence, they can unintentionally escalate a situation that really needed time, quiet, and clarity.

I care about this topic both personally and professionally. As the legal guardian for a sibling who has IDD, I’ve seen firsthand how impactful the right approach can be. The most effective and safest field interactions occur when responders slow down, adjust their communication, and intentionally bring the right supports into the situation.

This article explains why IDD needs a distinct crisis-intervention approach and how responders can tailor scene management, communication, and care pathways to reduce harm and improve outcomes.

What is IDD?

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are a group of conditions that begin before adulthood and affect learning, reasoning, adaptive skills, and everyday functioning. IDD includes diagnoses such as Down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and other developmental conditions.

While each individual’s abilities and needs are unique, people with IDD often experience differences in:

- Cognitive processing: learning new information may take longer, and complex instructions can be very overwhelming.

- Communication: individuals may use fewer words, rely on visual supports, or have difficulty interpreting abstract language.

- Sensory processing: lights, sounds, touch, or crowded environments may feel overwhelming or even painful at times.

- Adaptive functioning: routines, familiar items, and trusted people can be especially important for maintaining a sense of stability and predictability, which in turn reduces stress and supports emotional well-being.

It’s important to emphasize that IDD does not mean an individual is incapable of understanding or participating. Instead, it means responders must adapt communication and scene management so that the person has the best chance to succeed, remain safe, and feel respected.

The High Cost of Police Contact for People with IDD

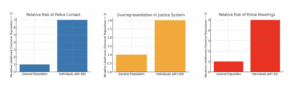

Research shows that people with IDD are significantly more likely to interact with law enforcement compared to the general population. Some studies suggest individuals with IDD are up to seven times more likely to have police encounters.

Once in contact with law enforcement, people with IDD face a heightened risk of deeper involvement in the criminal justice system. The United States Department of Justice’s Disabilities Among Prison and Jail Inmates, 2011–12, reports that individuals with IDD are disproportionately represented in police custody, jails, and prisons. They are more likely to be arrested, charged, and serve longer sentences compared to their neurotypical peers. Factors such as impaired communication, limited understanding of legal rights, and suggestibility during interrogation all contribute to these outcomes.

One of the most alarming disparities is the increased risk of police shootings involving people with IDD. The Ruderman White Paper on Media Coverage of Law Enforcement Use of Force and Disability explores multiple case studies of individuals with IDD involved in police shootings and specifies that individuals with disabilities account for one-third to one-half of those killed by law enforcement. Communication difficulties, atypical behaviors, and slower processing speed may be misinterpreted as defiance or threat.

Without specialized training, officers may escalate rather than de-escalate, with tragic outcomes. These concerning statistics underscore the importance of specialized training and protocols.

What Makes IDD Different in Crisis

Individuals with IDD process information, language, and sensory input in unique ways. Under stress, those differences widen. Rapid questioning, crowded scenes, bright lights, and conflicting commands can push a person with IDD into fight, flight, freeze, or complete shutdown. Recognizing these differences is key to safer interventions.

A Scene Flow That Works and Tactics to Reduce Harm

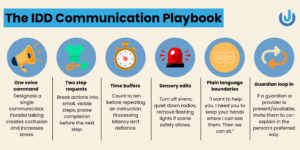

Rather than a checklist, think of a rhythm: Slow → Simplify → Support → Secure.

1. Slow the scene.

Lower voices, step back extra units and dim lights (if it is safe to do so), move onlookers, give clear requests, and add additional time between requests. Sirens, radios, bright lights, and multiple voices increase distress. It’s best to reduce stimuli whenever possible.

2. Simplify communication.

Designate one speaker. Use short, concrete phrases. Demonstrate rather than describe. Offer choices the person can understand (“Would you like to sit on the curb or under the tree?”). Allowing silence and repeating a straightforward instruction at a time can prevent escalation. Try to avoid crowding, metaphors, sarcasm, and rapid-fire questions.

3. Support regulation.

Caregivers, guardians, or familiar staff can help translate preferences, identify known comfort triggers, and recommend calming strategies to support individuals. Offer sensory aids (quiet space, water, a familiar item); avoid touch unless it is essential and explained.

4. Secure next steps.

Confirm understanding. Repeat the plan. Document known preferences and triggers so future responders have context.

These aren’t “soft” skills; they are safety tactics. Agencies that build them into policy consistently see fewer hands-on encounters and more voluntary resolutions. For policy foundations and training elements tailored to IDD, see the BJA model policy for interactions with individuals with I/DD.

Building Person-Centric Systems

Solutions lie in both officer training and building systems designed around the individual. Engaging agency partners to implement person-centric systems is essential, as collaboration between law enforcement, behavioral health professionals, and community partners is crucial. These frameworks ensure that officers are not responding in isolation, but within a network that understands and supports the individual’s needs with IDD.

IDD requires a different playbook because it requires a different lens. By recognizing the cognitive and behavioral differences inherent in IDD, law enforcement can shift from a reactive to a responsive model, one that’s grounded in preparation, understanding, and respect. Data sharing, care coordination, and cross-agency collaboration are lifelines that prevent unnecessary escalation and build safer, healthier communities. Julota’s article on Co-Responder & Crisis Intervention Programs describes how shared data supports safer interactions and follow-up.

Brief Scenario

Officers are dispatched to a welfare check involving a man pacing and yelling outside. Prior notes flagged his intellectual disability and sensitivity to lights, noise, and police presence. Units arrive with lights and sirens off; one officer and a co-responder make calm, simple contact while the second officer engages the guardian, who provides the client’s comfort items (blue water bottle, sunglasses).

Using short, concrete phrases, offering choices, and a “first–then” (“first water, then we talk”) approach, responders can reduce distress. They can learn that the incident was triggered by frustration when the client’s tablet died. What initially appeared to be aggression was, in fact, a moment of overwhelm and a loss of routine. This is just another reminder of how different the root causes can be when IDD is involved. Within ten minutes, the man accepts support, returns home with his guardian, and is referred to community services. The rhythm was: Slow → Simplify → Support → Secure.

When Custody Is Necessary

Sometimes, taking a person with IDD into custody is necessary. Even then, the IDD playbook should be utilized, as it reduces risk. Law enforcement, co-response, or EMS should explain each step before doing it, use the least intrusive control method possible, and never utilize face-down holds.

When arriving at the jail or hospital, law enforcement, co-response, and/or EMS personnel should ensure that they document the person’s communication needs, triggers, and preferences for intake or triage. Doing so reduces risk and builds continuity of care.

Closing

People with IDD deserve responses designed for the way they communicate, process, and regulate, not for the way we think they should or wish they would. Slowing down, simplifying, inviting supports, and sharing data is kinder for the individual and, even more importantly, safer for everyone. Different playbook, better outcomes.